Click to Skip Ahead

Like humans, cats navigate the world using their senses of smell, hearing, taste, touch, and sight. Cats’ vision is optimized for their crepuscular hunting habits. Cats can see better than humans in low-light conditions, but they can’t see well up close, and they need to be nearer to objects than people do to be able to see reasonably clearly, as their way to adjust their lenses to focus on nearby things is different than in humans.

Humans’ color vision is richer, while cats have an edge when it comes to seeing quickly moving objects. Cat vision is interesting in part because it’s so different from that of humans. Keep reading to learn more about how cats’ eyes work.

How Do Cats’ Eyes Work?

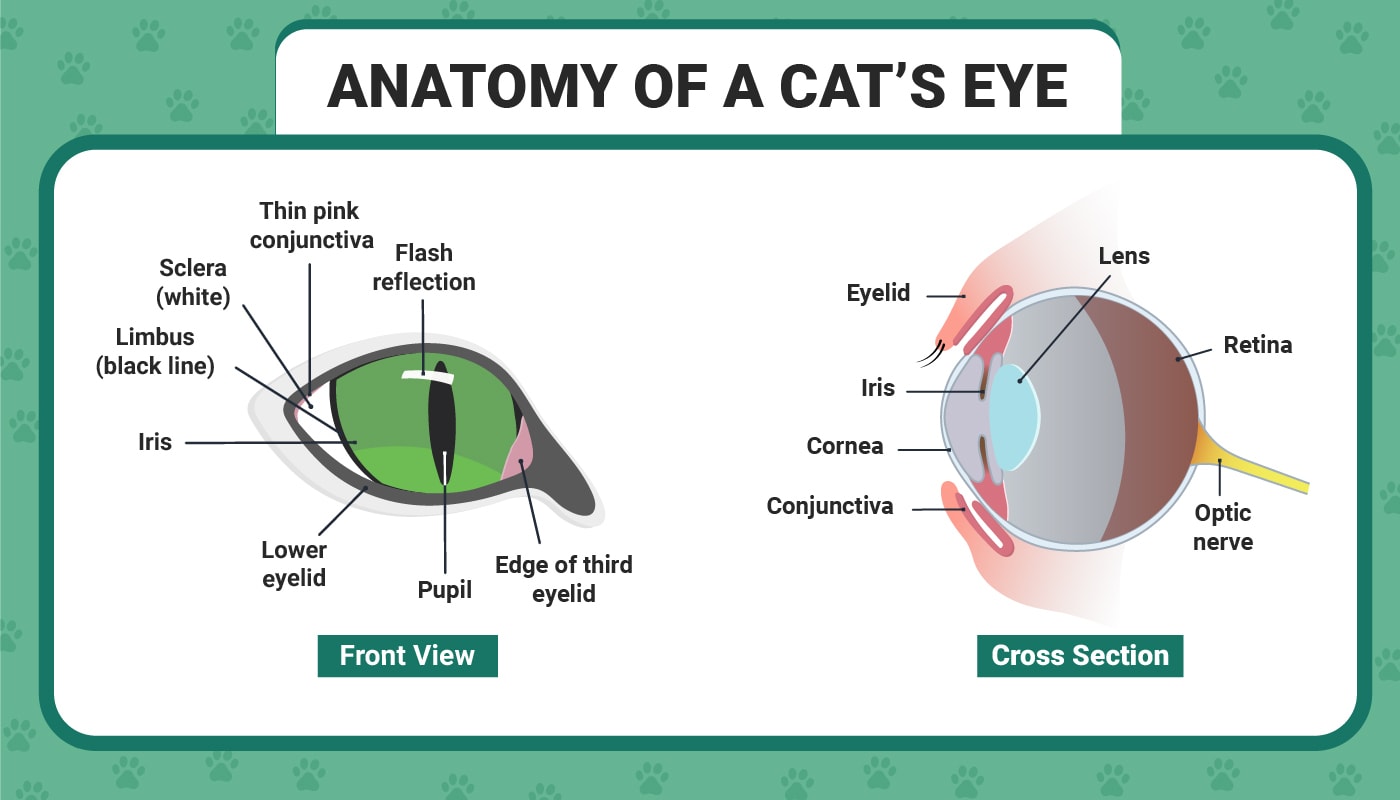

Cats’ eyes work much like human ones and include several parts, such as the sclera, conjunctiva, cornea, iris, pupil, and lens. They gather information that’s sent to the brain and interpreted as images. The eyeball sits in a bony socket known as the orbit, which also holds nerves, muscles, blood vessels, and tear ducts.

Third Eyelid and Tear Glands

Each cat’s eye has a nictitating membrane or third eyelid that provides additional protection by keeping their eyes moist and helping remove particles that land in their eyes. They also have lacrimal glands that make the watery part of the tears that help keep cats’ eyes moist. Tears are made of mucus, oil, and water, and the conjunctiva and eyelids also play a role in the tear-forming process.

Sclera, Conjunctiva, and Cornea

The conjunctiva, a thin semitransparent membrane, covers the sclera, or the white part of the eye. The clear, curved structure covering the front of the eye is called the cornea. It keeps the eye protected, allows the light to enter the eye, and provides an assist when directing light to the retina. In the retina, the light gets processed and travels to the brain to complete the process of vision.

Cats’ relatively large corneas contribute to their night vision by allowing lots of light into their eyes.

Iris, Pupil, and Lens

The iris is the colored part of the eye. Yellow, green, and blue are just a few of the eye colors commonly found among cats. The iris expands and contracts to enlarge or shrink the pupil, the “hole” in the middle that controls the amount of light in the eye.

The black opening in the middle of the eye is the pupil, which is opened and closed by a sphincter muscle. Cats’ pupils shrink in response to bright light and open to allow more light in darkness. When constricted, the pupil is slit-shaped, and as it opens, it takes on a rounder shape, permitting lots of light into the eye and giving cats a serious advantage when it comes to seeing at times like dusk and dawn.

The lens sits behind the iris and adjusts its shape to focus light onto the retina. Lens movement is largely controlled by the ciliary muscles, which contract when cats focus on nearby objects.

Retina and Tapetum Lucidum

The retina’s photoreceptor cells pick up light and translate it into electrical impulses. Each cell is linked to a slender nerve thread. The threads join together to form the optic nerve, which carries electrical impulses to the brain interpreted as visual images. The tapetum lucidum is located behind the retina, in the choroid layer, and enhances visual sensitivity under low light conditions as it reflects light back to the retina to give cats fantastic sight when it’s relatively dark.

Cones and Rods

Cats’ retinas feature two types of photoreceptor cells: cones and rods. Cones are great at picking up details, and they’re responsible for the ability to see in color. Rod cells pick up images in low light conditions exceptionally well and detect fast moving objects really well. The large proportion of these cells in the cat’s retina is one of the reasons cats can see so well at night.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Cat Vision

Cats see the world quite differently than people, at least partly due to the differences between feline and human eyes. Cats can see about six times better than humans in low light thanks to their tapetum lucidum and because they have more rod cells than people.

Night Vision

It also allows them to see scurrying creatures in dark conditions amazingly well, which gives cats an edge when hunting during their favorite periods of dusk and dawn. Because they have fewer cones than people, cats cannot see colors as intensely as humans.

Day Vision

Humans have better vision in bright daylight conditions, and cats need to be more than seven times closer to an object to see it as sharply as a human would do.

Field of View

When it comes to the differences between feline and canine vision, eye placement makes a difference in the way the two species see the world. Dogs have a larger area of peripheral vision than cats; however, cats have a wider area of frontal binocular vision enhancing their depth perception.

In both species the fact that eyes are located frontally means they have a large blind spot behind them. This is not the case with prey animals such as the horse, whose eyes are located laterally giving them an almost 360 degrees panoramic vision with a tiny blind spot behind them.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Do Cats Suffer From Vision Problems?

Yes, cats can experience problems when it comes to their eyesight. Some of the most common conditions include uveitis, scratches, retinal detachment, and cataracts. Uveitis is essentially a form of intraocular inflammation that’s often caused by infections such as feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), or feline leukemia virus (FeLV).

High blood pressure, caused by kidney disease and hyperthyroidism, for example, can cause retinal detachment. Cats can also develop cataracts; however, this is a less common problem than in dogs. Cataracts in cats often appear as a consequence of other eye diseases. They can also be present at birth (congenital) or be linked to old age or genetics.

Is It True That Cats Can See Ultraviolet Light?

A 2014 study demonstrated that some mammals, including cats and dogs, have lenses that allow some frequencies of ultraviolet light through, even without having UV-sensitive visual pigments such as some rodents and bats.

A cat’s visible light range rests between 400 and 750 nanometers. The ultraviolet section of the spectrum starts around 400 nanometers and goes all the way to about 10 nanometers. People have lenses that soak up light in the ultraviolet range and never reach their retina. That is why humans are insensitive to UV light.

Are Kittens Born Unable to See?

Yes. Kittens enter the world unable to see or hear. Their eyes are shut, and their ear canals are closed when they’re born. Most open their eyes when they’re between 1 and 2 weeks old.

Kittens all have blue eyes at first, and it’s possible to tell what color their eyes will be when they reach about 8 weeks old. Their ear canals generally start opening when kittens are about 10 days old, and the process is usually complete when they’re 2 weeks old.

Conclusion

Cats’ eyes are sensory organs designed to gather information and send it to the brain, where it can be processed and interpreted as visual images. They consist of several parts: the cornea, the “window glass of the eye”; the iris, or the colored part of the eye, which expands and contracts to allow more or less light into the eye through the pupil; the lens, that changes its shape to focus light onto the back of the eye; and the retina, which holds photoreceptor cells that are attached to nerve fibers that together form the optic nerve and take electrical impulses to the brain to be interpreted as visual images.

Featured Image Credit: dio arapogiannis, Pexels